In the late 1800s, after decades of violently removing Native peoples from their ancestral homelands and onto reservations, the US government set its sights on a new strategy — boarding school.

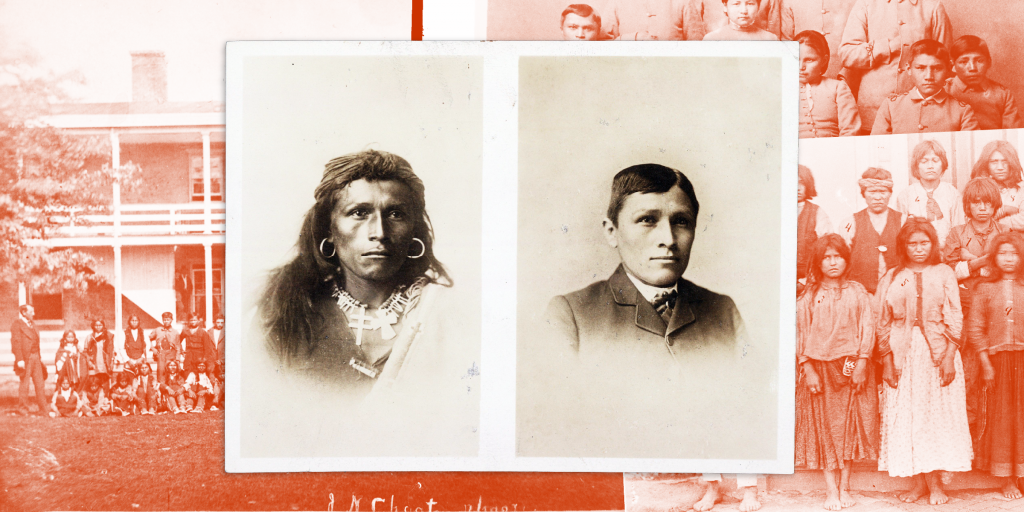

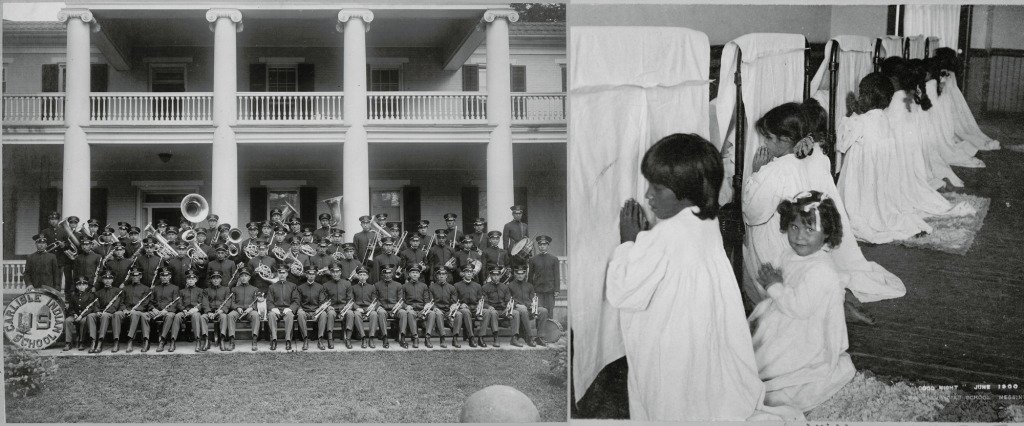

Starting in 1879, thousands of Indigenous children were torn from their homes and sent to faraway schools where practicing the cultures from which they came was essentially forbidden. The goal? To "kill the Indian" and "save the man," as the founder of the first such school phrased it.

The idea was that Native people could succeed in white American society, if only they left behind their traditional ways, but many of the boarding school students never saw their parents again.

Hundreds of children who died before they could return home remain buried in the schoolyard cemeteries to this day, some in unmarked graves. In some cases, the cemeteries themselves have been lost or redeveloped, with the old grave markers nowhere in sight.

Although they were viewed positively by reform-minded people who condemned the government's treatment of Native people up to that point, the boarding schools, and the US policy that guided them, can best be described as an attempt at cultural genocide.

"They were very denigrating of really anything having to do with Native life. Language, religion, hairstyle, the way you dressed, the way you baked biscuits. None of it was deemed worthy," K. Tsianina Lomawaima, a retired professor of American Indian studies who is the author of "They Called it Prairie Light: The Story of Chilocco Indian School," told Insider.

By 1903, at least 25 off-reservation boarding schools popped up around the country, primarily in the West, in addition to dozens of day schools and boarding schools that existed on reservations. It's estimated that tens of thousands of Indigenous children, coming from more than 100 distinct Native communities, passed through the boarding schools — some of which remain open.

Insider talked to historians and Native people who described a complicated history of the schools in which students had a range of experiences. To Lomawaima, the schools also represent resilience, given the Native cultures that persisted despite attempts to wipe them out.

Today, Indigenous nations and activists are still trying to understand the extent of what happened at these schools. Their efforts are largely focused on identifying the children buried on their grounds and determining how the US can reckon with this troubling chapter of its history.

Much of the 19th century was marked by the armed conflicts of the American Indian Wars, when tribes resisted US attempts to forcibly remove them from their lands. Treaties were made and broken, and tens of thousands of people were killed.

Capt. Richard Henry Pratt fought in the conflicts and, through his experiences with Native prisoners of war, came to believe that Indigenous people were not inherently inferior to whites and that in the "proper" environment they could become "civilized."

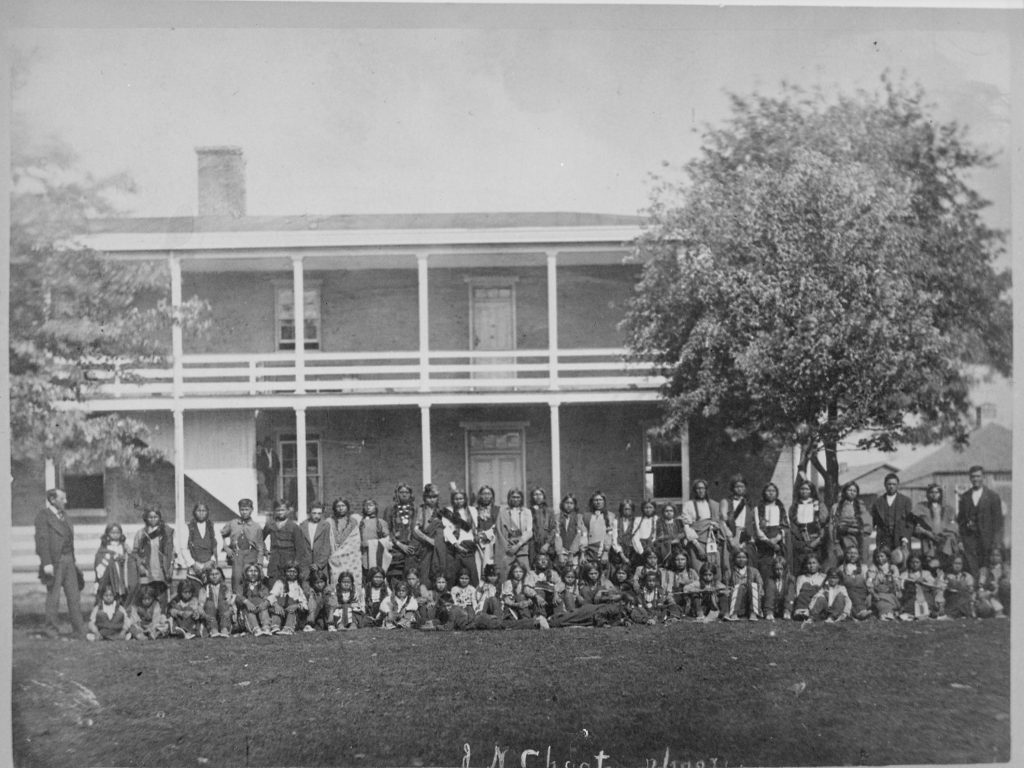

In 1879, Pratt opened Carlisle Indian School in southern Pennsylvania, the first off-reservation boarding school, inspired by the philosophy for which he is best known.

"A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one," Pratt said in an 1892 speech, referring to an infamous quote. "In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man."

Pratt's belief that Indigenous people were not inherently inferior made him somewhat radical for his time, when many of his contemporaries believed in the natural superiority of whites.

"At that time, the federal Indian policy was extermination or assimilation," according to Jean Keller, an archaeologist and historian who is the author of "Empty Beds: Student Health at Sherman Institute."

"It was believed that Indians were something of the past, that they weren't part of the modern world," Keller told Insider. "Pratt actually believed in the humanity of Indians."

Some viewed Pratt's goal for the schools — to assimilate Native people into American society — as a preferable and more humane approach to US relations with Indigenous people.

While assimilation was cited as the primary reason for the boarding schools, scholars say the US was also motivated by another potent force: the desire to take Native lands.

From 1887 to 1934, the US took more than 90 million acres, or nearly two-thirds of all tribal lands, and sold them to non-Native settlers.

"By the 1930s, the United States had accomplished what it set out to do at the beginning of the assimilation era: control reservation properties and turn them over to White landowners," Brenda Child, a historian and professor at the University of Minnesota, wrote in The Washington Post.

Historians have said the government decided education for Native people was less expensive than armed conflicts. In 1881, federal officials estimated it cost $1 million to kill one Indigenous person in battle but only $1,200 to enroll an Indigenous child in eight years of school, according to "Away from Home," an exhibit at the Heard Museum in Phoenix.

As boarding schools began to open far away from reservations, students came to attend them in a variety of ways.

"Certainly there was police force used in many instances, and by police force I mean armed officers going to Indian communities and taking children by force," Lomawaima said.

Families were threatened or coerced. Some gave permission for their child to go, though parents may have done so to help them escape the malnutrition and poverty plaguing reservations as a result of US policy.

"In the paperwork, that family or child chose to enroll," Lomawaima said. "But we really need to know about the forces at work in their lives. Did they have other options?"

Historical accounts show the splitting up of families was often a devastating experience for the students, some of whom tried to resist or escape while en route to the schools, according to the author and historian David Wallace Adams in "Education for Extinction."

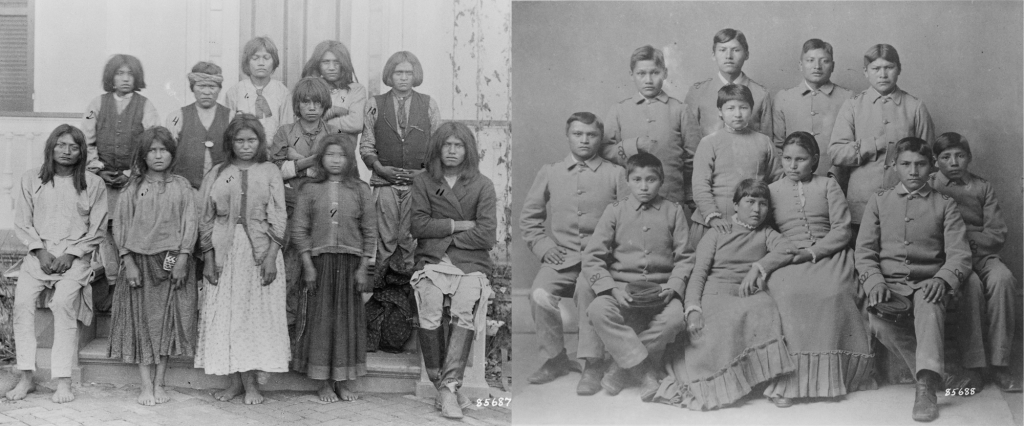

Once students arrived, they were prohibited from practicing their traditions, speaking their native languages, or singing their tribes' songs. They had to speak only English and attend Christian church services. They were forced to cut their hair, stripped of traditional clothing, and put into uniforms or other clothing that was considered civilized.

In some schools, kids were shed of their names and given "white" names instead, along with identifying numbers. The schools, especially in the early days, were militaristic in nature, inspired by Pratt's Army background, with students forced to march and stick to regimented schedules.

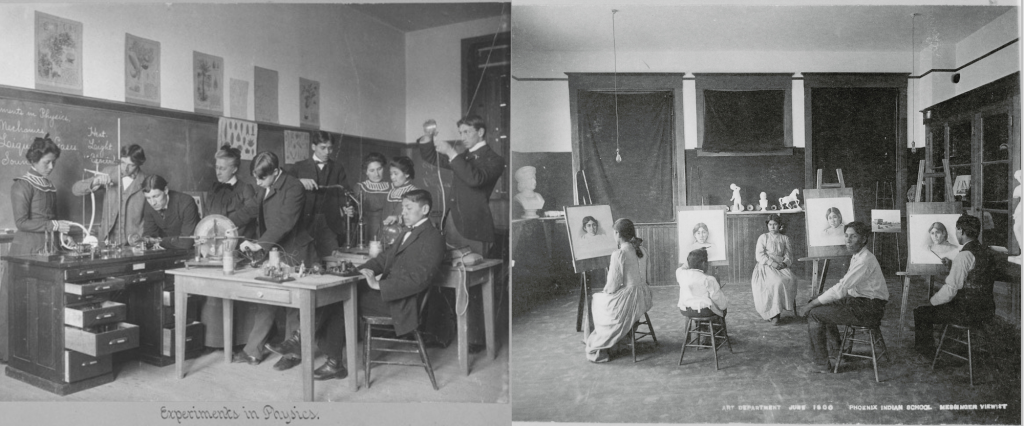

They were also industrial training schools, so in addition to learning things like reading and writing boys were taught trades like farming and blacksmithing while girls were taught domestic skills like cooking and sewing.

Perhaps the key feature of the off-reservation boarding schools was that they cut kids off from their families and communities by sending them hundreds or thousands of miles away.

On-reservation boarding schools and day schools run by the federal government also existed, and could satisfy the federal government's mandate that Native children attend school. But policymakers came to view the off-reservation schools as a more effective means of assimilation. As Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz explained to Congress in 1879: "It is the experience of the department that mere day schools, however well conducted, do not withdraw the children sufficiently from the influences, habits, and traditions of their home life."

Kids who attended schools on or near their reservations could go home for dinner. Their parents could visit. They were still connected to their cultures, which gave policymakers the idea that "whatever they were being taught during the day just got blown away at home," Keller said.

Students were discouraged from even visiting home on school breaks, or could go only if their parents could afford the train ticket. Some kids arrived at the boarding schools as young as 5 and didn't return home until their early 20s. Because students would be punished for speaking their native language, some lost the ability to speak them at all.

"They took their language away," Keller said. "When the kids did go home they couldn't communicate with their family anymore because they spoke English."

Though the historical records are incomplete, there are many documented accounts of student resistance, according to Adams. Students often tried running away from the schools, some repeatedly. Others would sneak away from teachers to tell stories they learned from their elders or speak in their native language in secret.

Students died from diseases, accidents, and other causes at the schools, according to Keller, who researched the health of students at Sherman Institute in Riverside, California, in the early 20th century.

Many students lived in cramped dormitories, slept two or three to a bed, and were underfed or malnourished. Schools were plagued by epidemics of tuberculosis, trachoma, measles, pneumonia, mumps, and the flu.

Students who died were buried in on-site cemeteries because the remote locations of reservations made it challenging to transport remains, with the government unwilling to pay for it.

Since the schools were federally run, records exist detailing what happened to some of the students who died. But in other cases, there are huge knowledge gaps or contradictions.

At Chemawa Indian School in Salem, Oregon, federal government records document 208 students buried at the school cemetery. But in 2016, a researcher discovered 222 sets of remains, with no existing records for the 14 that were unaccounted for. Some of the grave markers also didn't match the locations of the remains.

At least 180 Indigenous students were buried in the cemetery at Carlisle. Dozens more were buried at Sherman, where Keller ran into similar inconsistencies while researching the school cemetery. An old deed listed the cemetery as one acre in size, but today it's only a fraction of that. It's still unclear whether more remains are buried outside the official grounds.

There's also the nearby Perris Indian School, which closed in 1903 when Sherman opened. During her research, Keller dug up a photo from the 1950s that clearly shows a cemetery at Perris, but now "it's just gone."

"Now it's an industrial building and a parking lot," she said, adding that she used ground-penetrating radar to try to locate remains. "We know one girl for sure that was buried there, but there's nobody there now."

Unanswered questions about the cemeteries, who is buried in them, and what happened to them are at the center of many pushes by Native nations to investigate the schools.

In 2017, the Northern Arapaho Tribe of Wyoming became the first to successfully repatriate student remains from a boarding school, efforts that are shown in the PBS documentary "Home from School: The Children of Carlisle."

Jordan Dresser, a film producer who is chairman of the Northern Arapaho Business Council, told Insider that bringing the students home meant "reclaiming who we are" and was a way to "right those wrongs in a sense."

The heyday of the off-reservation schools lasted from the 1880s to the 1920s, during which time they were largely oppressive institutions. But even during that time, student experiences varied.

"They were institutions of violence for much of their existence, but not all people who attended those schools had traumatic experiences," Lomawaima said. "To say that the only consequences were trauma tremendously devalues the resilience young people brought to those experiences."

The schools changed significantly over the 20th century. By the time Matt Leivas, a Chemehuevi, attended Sherman from 1968 to 1971, many of the most oppressive school practices had been lifted.

Leivas told Insider many of the leadership skills he attained while at Sherman helped him throughout his life. He went to the school in part because his cousin told him it was a good place to play football, but when he arrived he was shocked by how lax the academics were compared with the public school he previously attended.

"I was adamant to make a change," he said, "to try and get more Indian teachers in there but also to improve the academics."

Leivas said his senior class of 1971 worked with the administration to improve the curriculum. Sherman became accredited later that year, changing its name from Sherman Institute to Sherman Indian High School.

"We were always pushing for change for bettering the school," Leivas said. "I'm very proud of that."

He did experience racism while attending Sherman — including referees examining Indigenous students' nails before games to ensure they wouldn't gouge people — but in the decades since he's maintained close ties to the school and other alumni.

Leivas also works on combating the cultural loss some Native communities experienced in part because of the boarding schools. He co-founded The Salt Song Trail Project, which is dedicated to preserving and revitalizing the sacred songs of the Southern Paiute people.

Even in the early days of the boarding-school program, students found ways to capitalize on their experience.

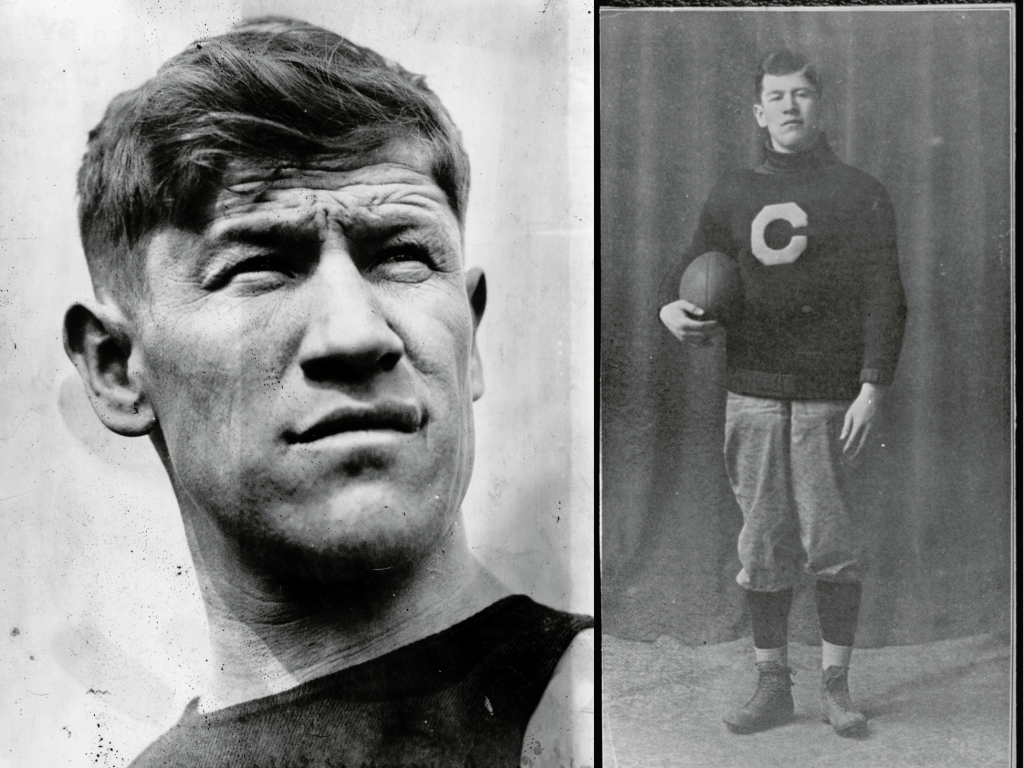

The best-known example is perhaps Jim Thorpe, who in 1912 became the first Native American to win a gold medal at the Olympics. A member of the Sac and Fox Nation in Oklahoma, Thorpe excelled in sports at Carlisle. He went on to play both baseball and football professionally and served as the first president of the organization that would become the National Football League.

Another student, a Paiute woman named Viola Martinez, used skills she learned at Sherman in the 1920s to read as much as she could to "prove myself to those people who thought my brain was different because I was brown and they were white," according to Adams. She became a social worker and teacher in Los Angeles, where she was a driving force behind founding the city's American Indian Education Commission.

Lomawaima said such stories didn't vindicate the flawed ideology behind the schools: "The fact that some kids survived it or even thrived in it, that doesn't absolve the institutions or the government."

The schools dramatically evolved over time. In 1928, an investigation commissioned by the secretary of the interior found students at the boarding schools were underfed, overworked, and harshly punished and that the schools were overcrowded and lacked medical services.

The Meriam Report, officially titled "The Problem of Indian Administration," led to reforms at many federally run schools for Indigenous people, with many off-reservation boarding schools closing in the 1930s.

The schools that remained open continued to change, though at different paces and with some setbacks, over the 20th century, especially in the wake of the civil-rights movement, as Native nations gained more control over the schools their children attended.

Four off-reservation boarding schools operated by the Bureau of Indian Education remain open.

Despite how schooling was wielded against them, Native communities saw the value in it and worked to implement curriculums that were meaningful to them and their children, Lomawaima said.

The boarding schools also represent one of the options Native families have today when choosing how their children should be educated — choices they didn't have in the past.

"Self-determination for Native people is not only on the level of Native nations but on Native people and families. It's important to have choices," Lomawaima said.

Today, the schools celebrate Indigenous cultures. At Sherman, students take classes on Native traditions like basketry, beading, and endangered Indigenous languages. A pow-wow is held every spring, and events are held for current students to visit the cemetery and place flowers on the graves.

In June, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, the first Indigenous person to serve as a Cabinet secretary, announced a federal boarding-school initiative to investigate the schools, in part a response to discoveries of unmarked graves at Canada's residential schools for First Nations children.

"While it may be difficult to learn of the traumas suffered in the boarding-school era, understanding its impacts on communities today cannot occur without acknowledging that painful history," Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna, said.

The investigation was expected to focus on the students who died and the lasting consequences of the boarding schools, with an emphasis on consulting with tribes on how to protect burial sites and respect the affected families and communities. A final written report was meant to be completed by April 1 but had not yet been released at the time of writing.

Haaland has also expressed interest in working with lawmakers to reintroduce a bill that would create a truth-and-reconciliation commission. Such commissions — official bodies to investigate and resolve past wrongdoings by governments — have been formed in countries around the world, including South Africa, Canada, Argentina, and Kenya.

Christine Diindiisi McCleave, a citizen of the Turtle Mountain Ojibwe Nation, said the process must begin with establishing the truth using historical records and testimony from survivors and their direct descendants. McCleave previously served as the CEO of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

"This is not just a problem for Indigenous people in the United States or Canada. This is not just a problem for North America," McCleave said. "This is a global issue about human rights, why governments continue to violate the human rights of certain groups of people."

Have a news tip or story to share? Contact this reporter at [email protected].